McMillan House

Built in the mid-1930s, Margaret McMillan House is an important local landmark adjacent to Platt Farm and accessed from the A227 Wrotham to Gravesend Road. The building is named after Margaret McMillan who dedicated her life to the developmental needs and educational progress of kindergarten and primary age children; she had a profound effect on England’s education system including the establishment of Margaret McMillan House.

The Original Property

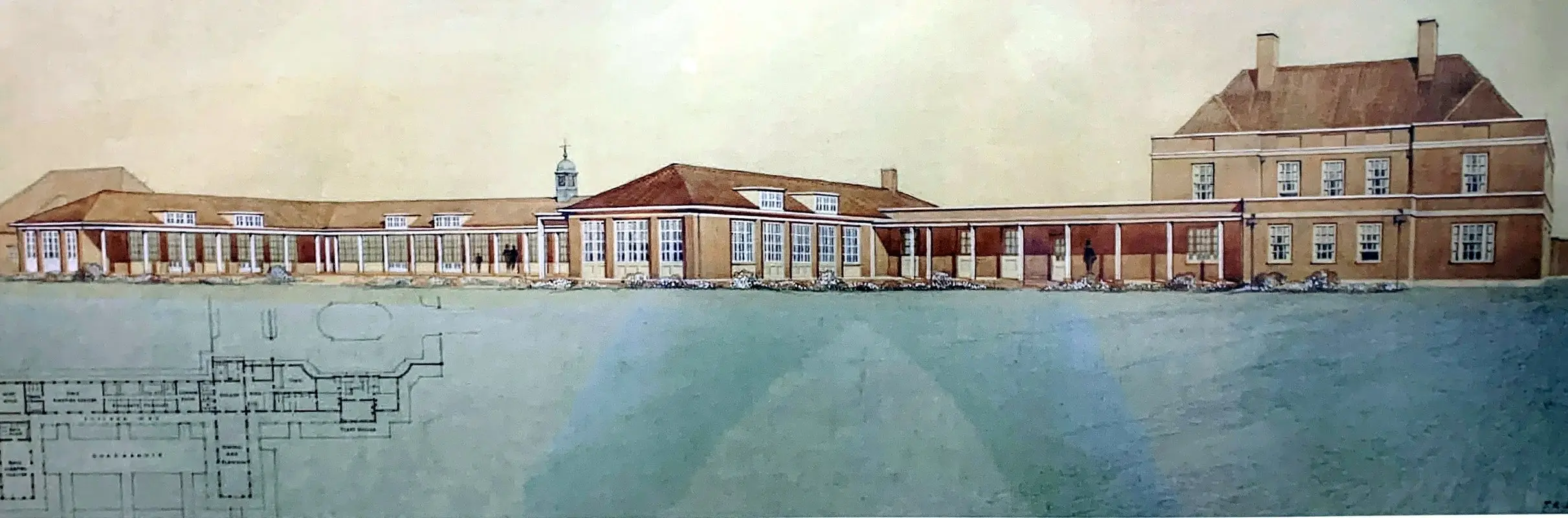

The following article is an extract from The Architect & Building News published in November 1936 and provides a description of the original layout of the property when first built. The original architect was H. T. B. Barnard (A.R.I.B.A.)

This house is in the nature of an educational experiment and is being run in connection with the Rachel McMillan Training College and the Nursery and Camp Schools at Deptford. Every year, from April to October, children come from Deptford in relays of forty to spend one month at the house, accompanied by their own teachers and six students from the training college.

The design has been governed by the need for a strict economy and low maintenance costs. It consists primarily of a paved courtyard, open towards the south. On the west is the boys’ dormitory, balanced on the east by the dining and play-room. The central block comprises the girls’ dormitory, students’ cubicles and common room, together with bath and lavatory accommodation and a quiet room. On the east is the staff house, the only part of the building not of single-storey construction, the children’s quarters having been planned at ground level throughout to facilitate escape in case of fire.

The staff house comprises accommodation for a resident warden, including a sitting room, bedroom and bathroom; for a married couple as caretakers, with a sitting-room, scullery and bedroom; a staff common room; a self-contained suite on the first floor, with a sitting room and bedroom, for a member of the training college staff; a bed-sitting-room for a member of the nursery school staff, an isolation room, two small bedrooms for visitors, and two bathrooms.

The staff house is connected with the main building by a covered way. In the north-east angle of the main building is the kitchen; this has been planned very spaciously, as here the students receive lessons in the cooking and serving of meals. Cooking is by means of an “Esse” heat storage cooker, burning anthracite.

The structure is of cavity brick walls, except where the covered ways occur. There are multi-coloured facing bricks, and dressings of artificial stone or patent rendering. The dormitories have open king-post roofs, lined with building boards. Hot water is supplied from a coke-fuelled boiler, while electric radiators for occasional use have been installed in the shelters, and there is an open wood-burning fireplace in the playroom.

Margaret McMillan

The history of how the committed socialist Margaret McMillan came to befriend the British Royal family in the person of the outwardly stiff and formal Queen Mary, consort to George V, and how together they gave substance to Margaret McMillan’s dream of liberating the down-trodden masses from the curse of bad housing, bad diet, and unambitious and under-funded education, is a remarkable story by any standards.

That it involved the personal commitment of Nancy Astor and generous donations from the Astors and others caught in the spell of Miss McMillan’s passionate embrace of a new kind of education for the very young, makes it extraordinary.

Sixty years before this, an early pioneer of the importance of a good and affordable mass education system, William Hickson, lived in Fairseat Manor, less than a mile from the eventual site of Margaret McMillan House.

Margaret McMillan, and her elder sister Rachel, were born in the United States just before the outbreak of the American Civil War, daughters of an emigrant Scottish family from Invernesshire. There was to be no American dream for the two young sisters. Their father died of scarlet fever in 1865 when Rachel was 5 years old and Margaret just turned 4. Their mother returned with them to Scotland, thrown back on the support of relatives. It also meant, fortuitously, they could be educated in one of the best Scottish schools, Inverness High.

In 1887 Rachel paid a visit to a cousin in Edinburgh and heard a passionate sermon on the subject of how Christian teachings could be the basis for a new and better society. She became a convert to Christian Socialism and moved south to London – where Margaret had found a job as a superintendent in a home for young girls – and she converted her younger sister to the new creed. They soon had an opportunity to make their mark. During the prolonged dock strike of 1889, they raised money to feed the families of the striking stevedores. In the process, they met some of the leading socialists of the day, intellectuals such as William Morris and Sidney Webb, and dedicated activists like James Keir Hardie, who went on to found the Independent Labour Party in 1894.

In 1892 they moved to Bradford, where Margaret pulled off her first political coup, working with Dr James Kerr, the Schools Medical Officer, to introduce the first medical inspections of schoolchildren anywhere in Britain. It was merely the first step in a thirty-year long struggle to lift working-class people out of the mire of poverty and ill health by breaking the cycle of deprivation.

A decade later Margaret was back in the east end of London and soon established herself as a visionary reformer. In 1908 she secured the opening of the first school clinic in Britain, in Bow, a place where parents could bring their kids of school age for free medical care. Two years later a second clinic on the same lines was opened in Deptford, home to some of the worst slums in Europe.

By now, Margaret McMillan had come to realise that it was the crucial pre-school years that mattered most if the life chances of the poor were to be transformed. The answer was to set up schools where the kids had a chance to thrive, through good food, stimulating teaching, and a healthy lifestyle. The first two were opened by Margret and Rachel in the heart of Deptford in 1910.

The most revolutionary feature was the provision of sleeping accommodation in airy shelters. Each child would be bathed in the evening, given clean night clothing and lulled to sleep with a bedtime story. The effect on children’s health was dramatic. In the first six months of the “camp schools”, one for girls and one for boys, there was only one case of illness among the 40 children enrolled.

The nursery building is still in use today as a nursery and Children’s centre. Over the years the premises have been updated but great pains have been taken to retain the layout and atmosphere of the building and play areas. Even today in the built-up area of Deptford it remains an oasis of peace and nature. Dick Hogbin, on behalf of Greenwich Council, was involved in a major renovation project in the early 2000s when it became a Children’s Centre and remembers the pains that everyone on the project team went through to keep Rachel McMillan’s original ethos intact.

All of this was financed by voluntary donations, mostly from wealthy patrons. The most remarkable of these patrons were to be found in Buckingham Palace. George V had come to the throne in 1910 and his wife, Queen Mary, was to become a life-long admirer of Margaret McMillan’s nursery school work. Queen Mary’s public support for the camp schools brought money flowing in. As a result, a much larger “open-air nursery” was opened in Peckham in 1914, this time with a training centre for nursery school teachers and nurses attached.

The bond was strengthened in the adversity of the war years of 1914 -18. The greatest setback was the sudden death of Rachel in 1917, a great loss since she had day-to-day management of the schools. In fact, the Deptford experiment may have ended in 1919 had not the Queen come to the rescue with an injection of funds.

In 1924 Nancy Astor appeared on the scene for the first time, introduced to Margaret McMillan by the first Liberal woman MP, Margaret Wintringham. Lady Astor, who had developed a keen interest in nursery school education, became a devotee of the saintly Margaret, who was approaching her 64th birthday but was remarkably young and vivacious when talking about something she really believed in. As far as Lady Astor was concerned, Margaret McMillan could do no wrong. The forces were now being lined up for the next move forward,

Margaret had long hankered after a memorial to her sister. What better than to build a new training college, teaching the new methods of education in a brand new building right in the heart of Deptford itself. It would cost at least £20,000, a vast sum those days, but with the support of the Astor wealth, and other benefactors rallying to the cause, all now seemed possible.

A substantial site was obtained in Creek Street and the building of what was to become the Rachel McMillan Training College was set in motion. It was officially opened by Queen Mary in 1930. For Margaret McMillan, it was the achievement of a dream. But within a year she was dead, a few months short of her 70th birthday.

A new trust was set up to consider a proper memorial to her life achievements. Nancy Astor was appointed to the chair, with a distinguished body of trustees to support her. It was pretty soon agreed that nothing would be better than a new version of the camp school, but this time set in open countryside within easy reach of Deptford. It would be opened up to Deptford children of pre-school and early primary school age, and used as a holiday home and a training centre for nursery teachers.

In 1934 an ideal site had been found, just outside Wrotham in Kent, high on the Downs. As well as the fresh air of the countryside, there would be an opportunity to pursue nature study and take long excursions in the woods. The site identified formed part of Platt House farm, Fairseat Lane, which was owned by Courtlandt and Grace Taylor. They had bought 123 acres including Platt House and farm buildings, from Mr and Mrs Lunt in 1925 for £6,000 with the aid of a mortgage. There was some link between the Taylors and the Astors and in 1933 Lady Astor took over the mortgage of the farm.

On 31st January 1935, Grace Taylor sold 21 acres on the southern edge of her farm to the Trustees of the Rachel McMillan Training College for £6,000. This sum, you might think, would be used to pay off the loan from Lady Astor but it seems not, for in 1941 the sum was still outstanding and ownership of the farm passed from the Taylors to the Astors. What remained of the farm was tenanted for some years and was then gifted to Lady Astor’s son, David who lived there until 1967.

One elderly lady, Lettice Floyd, who had been a long-time admirer of Margaret’s work for young children and was a prominent Suffragette, offered to leave £30,000 in her will to put the project on a good footing. This offer was gratefully accepted and an architect was instructed to draw up the plans. There would be a big house for the student teachers, who would be expected to stay for a stint of two weeks at a time to master the new teaching methods in a practical way, and a west wing for the young children of nursery age.

The project went smoothly and all was ready for the official royal opening as scheduled on May 5th 1936. Queen Mary, who had been invited to attend, unfortunately, had to cancel because of the death of her husband in January, leaving the future George VI to step in.

Official Opening – 5 May 1936

In early May of 1936, the weather in the tiny settlement of Wrotham in Kent was unseasonably warm and sunny – fitting for the occasion of a royal visit.

On that fine morning, a convoy of blue motor coaches came bustling through the village, horns hooting as they turned up the narrow road that climbed onto the North Downs. Inside the buses, little children and their parents from the slums of Deptford and many making their first-ever trip out of London were entranced by the ever-unfolding vistas; fields of cherry trees in full blossom, woodland glades where the sun glinted through a canopy of green, and glimpses of rolling country stretching far as the eye could see.

Near the top of the hill, the coaches turned into a narrow driveway. There before them lay a striking new complex of red brick buildings, a temple to the growing cult of open-air education. One student teacher who had accompanied the Deptford families and recorded the occasion for posterity noted the effect it had on the party: “We were almost silenced”, she wrote, “by the beauty and the rightness of its setting there among green trees and fresh fields.”

And it wasn’t just the building that caught the imagination of parents and children alike. The lawn in front of the house ran out to meet a giant paddling pool. And beyond the house stood a fine old wooden barn, converted into a playroom. In it and around it were the first residents of this new holiday home for deprived children, spick and span for the occasion: “There they were, (another was to write) small Deptford children cycling about on fairy cycles in the sunshine and playing in their big, airy day-room and all looking well and cheerful”

But there was time only for the most cursory survey of the spacious 20-acre site, for the main event was soon to begin. The brand new building was to have a royal opening. The official cars and an escort of motorcycles drew up in the yard and disgorged a party of VIPs, among them the Duke of York (soon to become King George VI when his brother Edward VIII abdicated his throne the following January) and Nancy Witcher, Lady Astor, the first woman ever to be elected to the House of Commons.

For all the dignity of the line-up, the chief memory recorded by Lily Lynn, then aged 9 and one of the older Deptford children, was charmingly brief and down to earth: “Lady Astor and a lady who was a princess were there, and I saw the Duke of York. He played with the little children. All the students laughed to see him and Lady Astor playing in the sand. We all picked bluebells in the wood. Then we came home, and all the little children saw us off.”

That a future king and the famous Lady Astor should find themselves together in a sandpit, surrounded by little urchins from Deptford, is itself a tribute to the educational pioneer whose work inspired the building of the outdoor centre at Wrotham.

The Post-War Years

Just as in the First World War, Deptford became a target for enemy bombs. This time there was somewhere to evacuate the nursery children. Many came out to stay at the country house near Wrotham.

After the war was over, things had changed. State-run nurseries began to be opened, and money to run the Wrotham centre was hard to come by. In 1960, the trustees chaired by Viscount Astor approached the LCC and suggested the college and the house should be passed to them to run. New rules on capital costs meant that independent educational facilities had to put up 25% of all capital costs, and the government was intent on expanding the Rachel McMillan College to meet the demands of the post-war baby boom. The Trustees simply couldn’t raise the cash.

The LCC took over the McMillan legacy in 1961, continuing to run the Rachel McMillan Training College as a training ground for primary teachers. But the tide was flowing against sending students out to Wrotham as part of their training. So the LCC transformed it into a field study centre for London schools. Unfortunately, this arrangement didn’t last.

In 1965 the LCC was succeeded by the ILEA. Shortly afterwards the Rachel McMillan Training College was amalgamated with the Goldsmiths’ College and became part of London University, while the training college building in Creek Street was passed to the Metropolitan University, who promptly converted it into student accommodation. The field studies centre at Wrotham was now just one of many that made demands on the ILEA budgets.

When the ILEA in turn ceased in 1990, the Charity Commission agreed to establish a new charity, the Margaret McMillan Field Study Centre Trust, to assume responsibility for Margaret McMillan House, with the Borough of Greenwich assuming the role as corporate trustee, effectively in charge of the whole concern. They found a building in a sorry state and much in need of investment. The links with Goldsmiths College had all but been lost. Not surprisingly the number of children visiting the Centre had reduced to a handful. The capital asset was transferred from the ILEA to Greenwich on the basis that it was held in trust for all 13 inner London Boroughs. This meant that if Greenwich decided to sell the premises and land the proceeds would need to be split 13 ways.

Greenwich set about changing things. The building was patched up and, with the support of Greenwich schools, the borough presided over something of a renaissance. By 2006 the centre was visited by an impressive 6,000 pupils.

But, for all that, the Council did not have the resources to restore the building to its former glory, nor indeed the funds to renovate the handful of other outdoor centres that they had inherited from the ILEA. It was a problem not confined to Greenwich and the neighbouring borough of Lewisham found itself in a similar situation.

In the light of reduced budgets, Greenwich looked to find an organisation that could not only run the Centre but who could also access outside funds for capital improvement projects and this is when discussions with the Wide Horizons Outdoor Education Trust started. It became clear that this was a viable route forward provided that some investment was made in the premises before transfer. Works were carried out to the main building and a new outdoor kitchen/shower block was constructed together with a reed bed sewage system. Around this time a large area of additional woodland (from the southern boundary down to the junction of Fairseat Lane and the Gravesend Road) was purchased by the Council and added to the House grounds.

In 2007 the two boroughs handed responsibility for their outdoor education centres to the new Widehorizons Outdoor Education Trust which picked up the torch left behind by McMillan and her many disciples and set about putting the complex at Wrotham to new uses in line with Margaret McMillan’s original plans.

Recent History

The Widehorizons Outdoor Education Trust was established in 2004 to provide inspiring, high-quality outdoor education. The Trust aims to transform the lives of young people and all who learn, work and live in Greenwich and Lewisham council areas. The Trust works with students, teachers, youth and community groups to provide a wide range of innovative and compelling outdoor learning experiences

which change lives.

Widehorizons holds in trust some of the finest outdoor education assets in Britain, including Margaret McMillan House in Kent; Tyn y Berth Mountain Centre in Mid Wales; Townsend Outdoor Centre in Swanage; Horton Kirby Environmental Centre in Kent and the Environmental Curriculum Service in South East London.

The Widehorizons trust is working in partnership with Futurebuilders England to breathe new life into the Centre so that it can continue to fulfil Margaret McMillan’s vision and provide the highest quality and range of outdoor learning experiences to the diverse focal community.

On 17 June 2012 the Duchess of Cambridge, Kate Middleton, visited McMillan House as the following newspaper report by Angela Cole reported at the time.

The Duchess of Cambridge paid a special visit to Kent today to meet youngsters as they experienced the countryside for the first time.

Looking relaxed and casual, Kate, who was wearing Zara jeans, a jumper, waistcoat and green wellies, helped the eight and nine-year-olds from King Solomon Academy in London cook dough balls over their campfires – and sampled some with jam.

She was at Margaret McMillan House, near Wrotham, for the morning visit to meet the children, who had arrived at the centre on Friday. For most, it is the first time they have seen the countryside or stayed away from home. It is also the first time the school, which is based in an area of high deprivation in North Westminster, where 70% of under-15s live in workless households, has organised a residential visit.

Kate, who has worked extensively with the Scouts, was perfectly at home sitting around a campfire and crawling inside a shelter the children had made with sticks and branches. She also spoke to two youngsters about their night under the stars. During their camp, the children, aged eight and nine, will sleep in teepee tents and take part in teambuilding exercises, such as rope and obstacle courses and a survival challenge.

Headteacher Venessa Williams, who is from East Malling, said: “It’s been very exciting. It’s our first camping trip and the first year we’ve gone outside of London, and then this visit is on top. They’re going to be very tired!”

Youngsters from the academy were keen to answer the Duchess’ questions. Head of the centre, Niall Leyden, added: “Kate was really fabulous. She walked around and talked to all the children. She was very at home with all the woodland activities; I would have her as an instructor here any time.”

The academy is supported by ARK Schools, which is backed by The Foundation of Prince William and Prince Harry, a charity set up by Kate’s husband and brother-in-law.

In early 2018 Widehorizons Trust revealed that due to increasing financial difficulties following a decline in business and rising costs, the Trust was at risk of closure. In order to survive, they restructured the organisation which included closing some of their centres in London, Kent and Wales. Despite significant efforts to raise funds, the Trust sadly closed in July 2018.

Following the unfortunate collapse of the Widehorizons Trust in July 2018 Greenwich Council has been considering the future of the premises. Whilst this protracted process takes place the building is currently occupied by ‘Property Guardians”. These are people who come via an organisation that specialises in making empty properties liveable for people who, for a wealth of reasons, live organised lives but need short term cheap accommodation. In return for this the guardians undertake to keep the property secure and in the same state as when they took it over.

Editor: Tony Piper

Contributors: Andy Forrester, Dick Hogbin.

Acknowledgements: Widehorizons Trust, Kent Online, Mike Penny – Friends of McMillan House.

Last Updated: 06 April 2022

The local Parish Notes contain a series of articles on Margaret McMillan published in 2022 by local resident, John Mattick. These are available to view by selecting the following ‘Parish Notes’ links.

Mike Penny was the CEO at Widehorizons Trust and is championing the ‘Save Margaret McMillan House Campaign’. Visitors to this website can register their interest by emailing [email protected] and can follow progress on Twitter @save_mmh