The death of Police Constable Israel May

The story of the death of Police Constable Israel May; the arrest of Thomas Atkins in 1873 near to the Horse and Groom, Stansted, and his subsequent conviction and imprisonment.

The following article is taken in its entirety from the book ‘True Crimes from the Past’ by W.H. Johnson (published by Countryside Books in 2005). All but one of the photographs have been added by the Editors.

1861

Mary Atkins was terrified. She was used to the arguments, to the shouting, to the bruises she had seen on her mother’s arms. It had been going on for the past two years in their little West Malling cottage, a cramped place, where there was nowhere to hide from violence. Mary had seen how her mother had suffered, had seen how her father raged. But today it was different, more frightening. Only a minute earlier Mary had gone downstairs when she heard her mother ‘squeak’, just to see what it might be.

When she went through the kitchen and into the washhouse, there was her father in a real state. He had a knife in his hand. And what can an 11-year-old do in such circumstances? She had taken to her heels and dashed next door to Mr Ridley’s but for all her hammering on the door and for all her shouting, there was no reply. And so she went back home. What else could she do? But now the kitchen door was locked. What was happening? She began banging on the door, calling out to be let in. But there was no reply. She went to the window. She saw her mother lying on the floor, her father bending over her, the knife to her throat. Mary ran off again. Perhaps she might get help from the Woolletts, their other neighbours, but only the three children were in that house so there was no help there. And next, she thought she would try Mrs Woodger. Surely somebody could help.

Shortly after this, only a minute or two later, Ann Smith, Mr Ridley’s housekeeper, heard what she was to describe as scratching at the door. And crying, too. Why she hadn’t answered young Mary’s earlier knocking and calling out is not clear. These were modest two-up, two-down cottages. It wasn’t as though Mrs Smith was at the far end of a mansion. Perhaps she hadn’t heard. Or perhaps by the time she went to the door Mary, in desperation, had gone off home again. But when she heard the scratching and the crying, she opened the door and found Mary’s mother, Betsy Atkins, staggering away. She was, as Mrs Smith said, ‘all over blood’. She went to see what help she could offer but now John Atkins appeared. He raised the knife, threatening her, and she was afraid for herself and could only watch as the injured woman made her unsteady way across the lane and into the clover field.

Robert Pearch, working in one of the nearby hop gardens, heard some kind of commotion and, when he went to investigate, found Betsy in the field. She was conscious but did not recognise him. ‘Who is it?’ she asked. Realising that he could do nothing to help, Pearch sent for a doctor and called for assistance from the neighbours. Then he saw Atkins at his back door and went to him. Atkins asked Pearch how his wife was, though not with any real concern for her welfare. After telling him how grave her condition so obviously was, Pearch asked Atkins what had happened. Whatever had happened, Atkins replied, not going into any detail, it served her right.

By the time Dr Pope arrived Betsy Atkins was already dead. She had two throat wounds and a stab that had pierced the jugular vein. Atkins had been by now arrested and taken to the Malling lock-up.

The following morning, Superintendent Hulse of the Malling Division went to speak to the prisoner. Atkins greeted him with, ‘Good morning. Is the woman dead?’ Told that she was, he said to the Superintendent, ‘I did it. I saw Barton looking through the window and, had he come in, it would have been prevented. I have seen Barton and my wife in bed together. I am very sorry for what has happened but it is now too late.’ A desperate man, then. A deceived husband, driven to murder at the thought of his wife in the arms of another man. Another of those age-old tales, what the French call a ‘crime passionel’. Or so it might have seemed to those who did not know the facts of the case.

When 42-year-old John Atkins from Malling faced trial at the Kent Assizes at Maidstone in July 1861 the court heard a distressing, tragic tale. True enough, over the past two years, there had been constant arguing, often long into the night. The neighbours could not avoid knowing what went on in the Atkins’ household, the rows, the penetrating cries, the shouts, the blows.

One Sunday about two weeks before the murder, John Ridley had heard screaming from the Atkins’ cottage. He had gone to see what was the matter. He had looked through the window and there was Betsy sitting at the bottom of the stairs, hysterical, in tears. She appeared to be half-naked. Atkins was holding her gown and shawl. Ridley shouted through the window, asking what was wrong but neither of those inside could hear him. Then Atkins had come outside to speak to him. He was carrying a knife. He couldn’t go on living with Betsy, he said. It was all 1oo much for him. Ridley had come up with a glib solution.

Why didn’t Atkins just leave her, he asked. Atkins had said that he had a great mind to run away but that he did not want to leave his children. At this point, Betsy had come out of the house, dressed once more, and the conversation between the two men came to a sudden end when Atkins went to her, seized her by the arm, and led her back inside. Once there, he tore off her dress and threw it on the fire. Ridley did not explain what happened after that but it must be assumed that the fracas continued and the whole village knew the details of all that had occurred.

Just a week before the murder Atkins had been to Peckham, staying the week with his brother Tom and his wife. Mrs Atkins told how her brother-in-law had arrived unexpectedly early on the morning of 7th July. Obviously distressed, he told them that he had been running away from the police all night. He said that his wife had been to the police about him and that if he were to be caught he would be locked up for life.

Throughout his stay at Peckham, Atkins suffered from headaches and he was frequently depressed. There were times when he would go into a corner of the room and stand listening to the voices that he was convinced spoke to him. At mealtimes, he would come to the table and take his food and then disappear to eat it elsewhere. He would sit in a chair at other times, praying for up to half an hour, begging that God would take him. One day when his brother Tom was out of the house, Atkins announced that Tom had been killed ‘up against a gate across a meadow’.

When his brother arrived home later, Atkins was surprised to see him. ‘I thought you was dead, Tom,’ he said. But it was Betsy who had taken his life away, he would say. And the old sexual jealousy, the delusion of the woman’s unfaithfulness, would crop up time and again. It was all the fault of George Barton from Town Malling: he had found him in bed with his wife. This is what he constantly said, what he firmly believed.

During Atkins’ absence from home, another neighbour, Mary Stevens, had been to visit Betsy. No sooner had Mrs Stevens arrived than Betsy had fainted and their subsequent conversation suggested that she was exhausted by the constant quarrelling. Mrs Stevens spoke of the bruises on Betsy Atkins’ arms and the endless arguing that had been going on for the past two years. When Betsy’s uncle had come to stay with them for a while Atkins had become convinced that she and her uncle had had a sexual relationship.

Only an hour before the murder, Hester Ifield had called at the house and had found Atkins sitting by the fire and Betsy writing a letter. Atkins told her his head had been very bad all day. Betsy had been up with him for much of the night.

Such was the tale told at the trial of John Atkins, who in the end was declared unfit to plead and was sent to a mental hospital. But what can have been the effect on poor Mary and her other sister?

And what about the effect upon 15-year-old Tom Atkins, the only son?

It is impossible to say but young Tom, twelve years after his father’s trial for murder, also found himself at the Assizes on a charge of murder.

1873

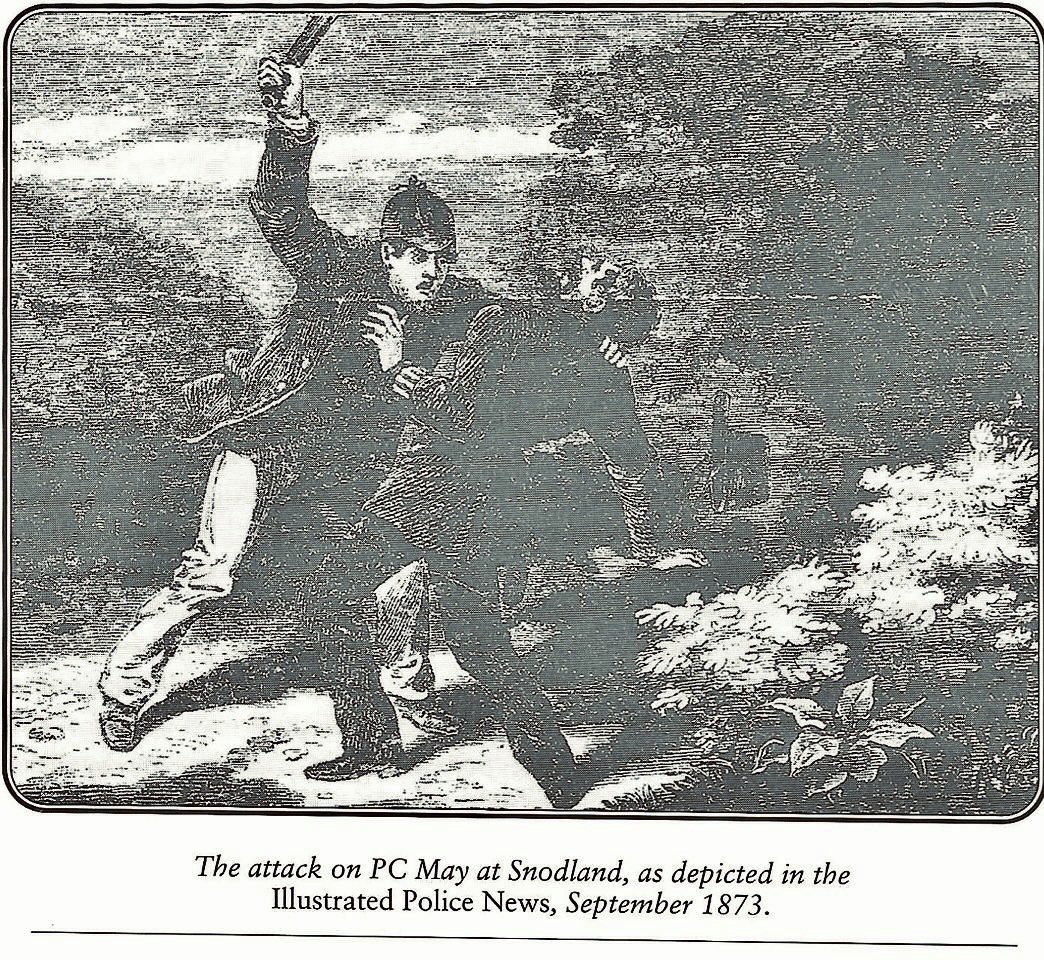

Early in the morning of Sunday, 24th August 1873, Samuel Stone, a bricklayer, going to work along the Snodland-Malling turnpike road, noticed quite obvious signs of a bloody scuffle in the road. And clearly, someone else, William Imms, had seen the signs because he was already peering around, looking into a turnip field. Then the two men came across a body, fearfully battered, bloodied, mangled, not 20 feet from the road. The corpse of a well-built man was stretched out nearly at full length, one leg slightly drawn up, an arm extended as if to protect the head. The face was smashed in, the features indistinguishable, the head shattered to pieces, the brains protruding, portions of it scattered over the ground.

The dead man wore a police uniform though at first, that was scarcely obvious, so covered was it in mud. The officer’s helmet lay some feet away from the body. His truncheon was nowhere to be found and it was assumed by Superintendent Hulse, still with the Malling Division, that it must have been the murder weapon. The policeman’s watch had stopped at 2.40 am, presumably during the savage struggle that had taken place.

There was little in the way of clues to the assailant’s identity although he had left a bloodied cap in the hedge. The wretched victim on the other hand, despite the savage beating he had taken, was too readily recognised. It was PC Israel May, the local policeman. Whoever had overcome this father of three must have been of phenomenal strength unless, as the Kent and Sussex Courier opined, May had been surprised by ‘his barbarous assailant. The policeman was extremely powerfully built.

The body was taken to the Bull Public House at Malling where the local surgeon carried out the post-mortem. He found a large wound on May’s forehead and a larger one at the back. It was one, or both, of these blows that had proved fatal but there were other injuries. The constable’s nose was broken and his left cheek was shattered. He had bled from the left eye and ear. There was severe bruising on the right elbow as though he had attempted to deflect a blow to the head.

The inquest held at the Bull, West Malling on the Monday produced a verdict of wilful murder by a person or persons unknown. But were there any possible suspects? There was talk of a couple of Royal Engineers in the area and they needed to be found. They had been staying at the Nag’s Head but had now left for London. While the enquiries about the two soldiers were being made, Superintendent Hulse continued talking to local people, trying to piece together PC May’s last hours.

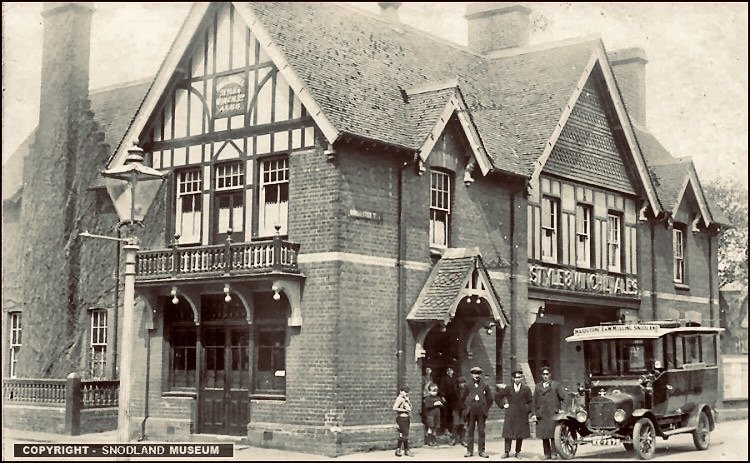

At 10.45 pm on the Saturday night, the constable had been seen talking to a man slumped against the wall of the Bull Hotel, Snodland apparently incapable of walking. May had advised him to go home but there had been an altercation, in which the two Royal Engineers had been involved. What part they had played and whose side they had taken is unclear but the situation cannot have been too serious for May shortly went on his way to deal with another minor emergency in the village, leaving the drunk still propped against the pub wall.

Shortly afterwards the drunk and the two soldiers, as they later testified, had left the public house together, walking towards Ham Hill, Snodland. But finally, it was too much for the drunken man who fell down in the road and, despite the best efforts of his companions, he could not be roused. And so he was left at the roadside to sleep it off. Shortly afterwards at about eleven o’clock May had come upon the man’s recumbent form and had tried to rouse him, with no success. He had left him where he had found him and had continued his patrol.

PC May was last seen alive at Ham Hill, a mile or so from the scene of the crime. At about 1.30 am he had spoken briefly to Mrs Selina Upton, wife of a local beer-house keeper, and had then gone on towards Snodland. The involvement of the two soldiers was soon clarified. They were picked up in Whitechapel and returned to Snodland where they gave an account of their night out, after which they were discharged for lack of direct evidence.

But now it was the drunk, a local man, 27-year-old Thomas Atkins, who was being sought, though how a man so profoundly inebriated could have got the better of a supremely fit and strong man like Israel May was a matter of some surprise.

Edward Baker, the ferryman at Snodland had informed Hulse that on the Saturday evening sometime after eight o’clock he had ferried Thomas Atkins over the river from Burham where he lodged. According to the ferryman, Atkins was already inebriated and uttering threats about what he intended to do when he met the constable. There was a history between the two men for Atkins had been arrested more than once by May for disorderly behaviour when under the influence.

But if Atkins was now the suspect he was nowhere to be found. He had left his lodgings at about eight o’clock on the Saturday evening, telling his landlord that he expected to be back at about eleven but he had not been seen since. Nor on the Monday had he turned up at the local cement works where he was employed as a labourer. A reward of £100 for information leading to his arrest was now offered.

It was not until Friday that the police had any clue as to the missing man’s whereabouts. On the previous Tuesday, three children, gleaning in a wheat field, had seen a man with a bandaged head in Birling Lees Wood, no more than a mile from Snodland. He had run into the open across a clearing to a smaller wood. Although at the time they had thought his actions strange, they had not realised that he was being sought by the police and consequently had not thought about telling anyone about what they had seen. Only on the Friday had they the slightest idea that the man was a fugitive and only then had they reported it.

By the time the police searched the wood Atkins was nowhere to be seen. But May’s missing truncheon was found there. This was another indication that the police were seeking the right man.

On Saturday, 30th August (six days after the death) Superintendent Hulse received a telegram from a policeman stating that Atkins had been seen that morning at the Horse and Groom in Stansted and that he was now on the road to West Kingsdown. Shortly after this, a local policeman came upon the wanted man sitting on the side of the road. Atkins was arrested and put up no resistance. He was worn out and starving and he asked the policeman if he would give him some of the bread and cheese he had in his pocket.

[Ed. From another account, it seems that early on the Saturday morning Atkins had begged for something to eat at the Horse and Groom and had been recognised by the ostler. He had been on the run for six days by then and, no doubt was ravenous. The ostler gave information to the police and shortly before eight o’clock Superintendent Hulse received the following telegram from I.C Girton, “Atkins just seen by a man who knows him. Gone by the Horse and Groom. We are close upon him. There are no marks upon him.” The next person who saw Atkins was a carrier of West Malling plying between there and London named Hayes who met the prisoner going towards London near Kingsdown. Hayes hurried on to Kingsdown and luckily found Constable Eudon at home, he having been up all night. Euden at once followed on the track of the now doomed man and arrested him without meeting with the slightest resistance.]

At first, when he was hiding in the wood, Atkins said, a man had given him some food but since then he had not eaten. His clothing was heavily stained. He had tried to wash out the marks of blood but had had little success. Some stains he had tried unsuccessfully to get rid of by rubbing them with chalk

Atkins was taken to Malling where he was charged with murder, yet it must have been a puzzle to Superintendent Hulse how this man of a quite slim build and shorter than PC May by several inches had managed to overcome the sturdy policeman. But Atkins’ previous work as a bargeman, pulling barges along the river, had developed his arms and hands, giving him a quite abnormal strength. Even drunk he had been able to outfight the constable.

Atkins was charged with murder by Superintendent Hulse. Shortly afterwards he asked if he might speak once more to the Superintendent, who went to the cell where the prisoner was held. Atkins was warned that anything he might say could be used as evidence at the trial but Atkins insisted that he wished to give his version of what had occurred. He expressed regret at what he had done but said he had had no idea he had killed PC May. He did not deny that he had fought the policeman but he resolutely rejected any suggestion that he had set out to kill him. Indeed it was not his fault, he said. He hadn’t started the fight. He had, he admitted, struck May on the head half a dozen times but it was in response to what he claimed was a violent blow to his own head.

At his trial before Mr Baron Pigott at Maidstone in December 1873, Atkins’ statement in prison to Superintendent Hulse was central to his defence. ‘I was lying along by the road’, he said, and the constable came and shook me. I got up and the constable then struck me on the head with his staff and made the wound you see here [pointing to a contusion on his head). We struggled together and fell through the hedge into a field. We continued to struggle there, and I took the constable’s staff from him and hit him about the head. I threw the stuff away, I don’t know where. I should not have done it if the constable had not interfered with me. That is the truth, so help me God.”

There was no conclusive forensic proof that Atkins had been in a bloody struggle with the policeman. His clothing had been sent to Dr Thomas Stevenson, at the Royal College of Physicians. After examining the garments the doctor stated that the blood might be that of an ordinary domestic animal. It is impossible in the present state of science to distinguish with certainty between the blood of a human being and that of an ordinary domestic animal.’ [Ed. Interesting that forensic science 150 years ago was unable to distinguish between human and animal blood but the nub of the case was not about such evidence as a scuffle had been admitted by the defendant. It rested on who had struck the first blow]. It was the defence case that the wound on Atkins’ head was consistent with his account that the constable struck him first. The defence did not dispute the fact that the accused had used the constable’s truncheon; in fact, that served as proof that he had not sought out May, ready prepared with a weapon to assault him. As for the witnesses who spoke of hearing Atkins making threats to deal with the policeman, these, the defence claimed, were made by a drunken man. What had happened, Atkins’ counsel declared, had not been premeditated. The defence alleged that the evidence against Atkins would not support a charge of wilful murder but it was accepted that it was consistent with manslaughter.

In his summing up Mr Baron Pigott directed the jury to concentrate on one question: did the accused set out with the deliberate intention of taking the life of PC May? They were to bear in mind that the only occasion on which he had shown malice against the policeman was when he was drunk. The words uttered by a man in drink, the judge pointed out, had not always to be taken at face value. They might be regarded as no more than empty threats.

That the weapon had been wrested from the constable was significant, said the judge. This indicated that Atkins had not furnished himself with a weapon beforehand, which might show that there was no premeditation. Finally, he directed the jury to consider whether Atkins was telling the truth when he said that PC May had struck him first. If the accused was telling the truth, then the constable had committed an unlawful act. In his Lordship’s opinion that would be material when the jury came to consider their verdict.

[Ed. Israel May was 37 at the time of his death and had been a police officer for 14 years or so, having joined the Kent Constabulary in 1859 two years after its formation. He was not a perfect officer. He had risen to the rank of Instructing Constable but with two others had been demoted to Constable Second Class due to a number of undetected burglaries in his area. Captain Rushton said at the trial that he had known Israel May since he joined the Force 14 to 15 years before and his demotion had nothing to do with violent behaviour.

It is clear that both Thomas Atkins and Israel May were well known in the area and the court had also heard about Atkins’ father and about other members of his family, a grandfather and an aunt, both of unsound mind. These were undoubtedly important elements that the jury members carried with them into their deliberations.]

After 20 minutes of consideration, the jury returned a verdict of guilty of manslaughter. Asked if he wished to say anything before the sentence was passed, Atkins expressed his remorse, repeating that it had not been his intention to kill PC May. In passing the sentence, the judge expressed his strong disapproval of any resistance to an officer under any circumstance even though that officer might be exceeding his duty. He said the jury had believed Atkins’ statement the policeman had struck him first and that mitigated in some degree the seriousness of the offence. He could not but believe, however, that Atkins had continued to rain blows upon May’s head long after he must have known that he was seriously if not mortally, wounding the policeman. It was, he said, an aggravated case of manslaughter and sentenced Thomas Atkins to 20 years of penal servitude [Ed. he was sent to HM Convict Prison, Princetown, Dartmoor]. He served fifteen years, after which he emigrated to the United States.

Like his father 12 years earlier, he had escaped the gallows.

Israel May was buried in Snodland churchyard. A huge procession followed the coffin from the Bull Hotel Snodland where the body lay. At his funeral service, the Rector reminded the mourners that ‘few can imagine what dangers a policeman has to face, while his fellow-creatures safely sleep.’ An appeal fund was raised later in which the rector wrote of the constable, ‘he was a man as good as he was brave … It needs to be known that his widow is in every way worthy of a devoted husband.’

Author: W. H. Johnson

Editors: Dick Hogbin, Tony Piper

Contributors: True Crimes from the Past by W.H. Johnson – Countryside Books pub 2005.

Acknowledgements: Find a Grave.com, Snodland Museum, Kent Messenger, Illustrated Police News, N. Chadwick, Fairseat Archive.

Last Updated: 11 January 2022