Earthquake in the Stansted area - 1860

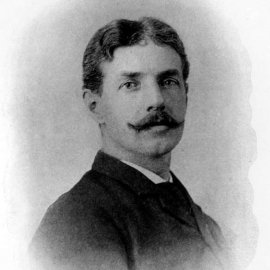

The following is an account in the Kentish Gazette of an earthquake in the Stansted area on 3 September 1860. The author is William Edward Hickson who was an author and lived at Fairseat Manor. He mentions the effect of the tremors on a man picking peas in Stansted.

Editor’s Note: Further information on William Hickson may be found under ‘Luminaries’ in the ‘People’ section of the website.

On Monday, September 3, this neighbourhood, and as it now appears a considerable part of Mid Kent, was alarmed by a shock of violent explosion, followed by a storm of hail and rain of unusual severity. The morning had been fine, with the barometer steadily rising, as it had done, after a long depression, the two days previous; so that the difference in the height of the mercury between Saturday and Monday, at 9am was fully an inch. Fahrenheit’s thermometer indicated no further wavering of the temperature, standing in the shade as on the day before at 60, and wind blowing from the north-east, a dry quarter; we had decided in our minds against the probability of any unfavourable change in the weather for the next 24 hours.

At 3 o’clock however in the afternoon, the inmates of every house in this hamlet, and those of every village and town for some miles round, were startled by a violent shaking of doors and windows, accompanied by a noise, which to some sounded like the rumbling along a road of heavily loaded waggons, and to others as if the roof were falling in, or some heavy piece of furniture was being rolled overhead.

The vibration was sufficient in the house of one of my neighbours to shake a hammer and some other articles from the kitchen shelves, to the great consternation of his domestics, and to cause the horses in our stables to neigh loudly, and struggle hard to get loose. Out of doors there was a tremour of the ground, but of a less strongly marked character. After the shock, the duration of which was probably 20 seconds, the clouds were observed to gather, and at a quarter to four discharged, with some thunder and lightning, first a shower of hail of the largest size (some with us having been picked up as large as marbles), and then a perfect cataract of rain, the heaviest seen this year, which is saying much, considering the quantity that has fallen.

This storm had a limited area, commencing about Nurstead and going off in the direction of Tonbridge. A few drops only fell at Cobham, and none at Ash, villages 10 miles apart, although the roads between were deluged with water. At East Peckham, between Tonbridge and Maidstone, the lightning struck and destroyed the spire of the church, doing at the same time serious injury to the town.

The cause of the shock preceding this storm was at first ascribed to blasting operations at Cuxton, near Rochester, for which preparations had been made, and this was so strongly my own impression that on Sunday I visited Cuxton, with a scientific friend from Guys to inquire into the fact. At Cuxton however, we learnt that there had been no blasting there on the 3rd, and that the operations carried out on the 7th for blowing down a chalk cliff had produced no sensible effect at the distance of a hundred yards; but the shock we heard and felt on the 3rd, was heard and felt at Cuxton, and was referred to the supposed explosion of a powder mil at Tonbridge.

In some places reports were current of a powder mill having been blown up at Sittingbourne, in others at Dartford; but no accident of the kind anywhere during the week has been announced and as it now appears certain that the shock must have had either of a meteoric or telluric origin, all the particulars that can be collected of it, as connected with the extraordinary characters of the season, become of interest.

A local paper says that on the day in question ‘the attention of Mr Flint, of Mill Hall near Aylesford, was suddenly arrested by strange rumbling noise, and immediately afterwards the house began to shake so violently as almost to threaten the destruction of the building. At the same moment the servants came rushing in from the kitchen, greatly alarmed, stating the earthenware was clattering on the shelves. The effects of the shock were still more perceptible on a large heap of coals in a shed at the back of the premises, and a man who was erecting a wall there states that it rocked to and fro in such a manner that he expected every moment to see it fall the ground.

The same extraordinary vibration was experienced at various other places, chiefly as our reports would seem to indicate in the country between Maidstone and Farningham. At the former town it was felt in different directions, and still more distinctly at Malling; while our Sevenoaks reporter states that, in some instances, even the house bells in that town were set in motion, and the turret bell at Knole House was suddenly rung to the dismay and consternation of the inmates.’

Statements to a similar effect reach me daily. Our medical authority communicates the case of a poor woman, a patient, who having experienced earthquakes abroad, rushing out of her cottage with her children, expecting it to fall, as she had seen houses fall in Peru. Mr Durling of the Plough, Meopham, standing on a haystack, felt the stack give way beneath him, while at the same instant, a lad assisting him near the stack cried out ‘the ground is moving’.

At Stansted a man who had been employed in cutting peas, and was sitting on the ground, feeling the shock, started on his feet from the surprise it occasioned. At Borough Green some bricklayers, at work at a new school room there building, saw the sand falling of itself from a heap they had deposited for mortar. Earthquakes have not been common in Kent, but they are not confined to volcanic districts; and if the cause of earthquakes be sometimes, as supposed, a disturbed state of the electric currents, and an effort of nature to restore their equilibrium, this is certainly a year to account for their occurrence, even on chalk downs.

The weather has been remarkable, and remains so. On these elevated lands we have still large breadths of corn uncut, and which shows no signs of ripening, from the deficiency of heat. Today, the 12th of September with a bright sun, my thermometer in the shade stands at 1pm, but at 56; and we have had white frosts this week for three nights in succession Kent has lost almost totally this year three of its staples – fruit, potatoes and hops. Oats will be a fair crop, but the wheat greatly below an average, except on warm sandy soils, and we have a proverb that:

When the sand doth feed the clay

Then for England well a day!

Yours truly

W E Hickson

Author: Dick Hogbin

Editor: Tony Piper

Contributors: N/A

Acknowledgements: N/A

Last Updated: 03 November 2019