Kurt Hausberg - 'The Man Who Fell to Earth

This article is about Kurt Hausberg who was an observer in a Dornier light bomber during a raid on the London docks on 15th September 1940. His plane was badly damaged and he baled out over Stansted but was killed on impact with the ground. Coincidentally he landed in a field that had been used during WW1 as a military aerodrome. His aircraft carried on and landed on Barnehurst golf course and the pilot was arrested. Unfortunately, a bomb that had been on the plane exploded killing at least five onlookers and wounding many more. After he was arrested, the pilot of the bomber Herbert Michaelis (22) was taken to Trent Park near Cockfosters, N London for debriefing and was the subject of an intelligence report by Squadron Leader Denys Felkin, the father of Anne Walton who, for many years lived at Stansted Lodge Farm, Tumblefield Road, Stansted. The full story of Denys Felkin can be read on this website under People>Recollections>Anne Walton.

Kurt Hausberg was buried in the Stansted churchyard before being exhumed and reburied 22 years later in the Cannock Chase German Military Cemetery, Staffordshire.

We are fortunate that Nigel Staniford has researched and written a full history of the ill-fated flight and the German airmen involved. Much of the information in this article has kindly been provided by Nigel whose uncle lived in Barnehurst and who witnessed the Dornier aircraft flying low over the rooftops before landing on the golf course.

The following is a summary of the events of the day and the people involved. Some of Nigel’s detailed research has been omitted by the Editor and is available in the Stansted and Fairseat history Society’s online archive.

The Raid

Sunday 15th September 1940 was a fine but cloudy day that was to become known as Battle of Britain Day. It was a make or break point for the Luftwaffe as so far they had not broken the RAF and this had to be done to allow the planned invasion of Great Britain (Operation Sealion).

The Luftwaffe sent over various raids on the 15th, but the incident which was witnessed by Nigel Staniford’s uncle happened in the afternoon of that day. After returning from the morning raids various bomber and fighter units started to refuel and rearm as other units got ready to take off.

Aircraft from Boissy-Saint-Leger, Cambrai, Antwerp, Lille, Wevelgem and Gilze en Rijen took off and headed towards England their targets being the West India Docks and Royal Victoria docks north of the Thames as well as the Surrey Commercial docks to the south. Fighter cover was provided by Me109s and they met the bomber force over Calais and headed for England. It was a formation of 475 aircraft.

Some of the fighters stayed close to the bomber formations as Reichsmarschall Goering had forbidden the fighters from leaving the bombers. This was not popular with the German fighter pilots as they had to fly slowly to stay with the bombers, and made them easy targets for the RAF fighters who would take advantage of attacking the slow-moving fighters.

RAF squadrons were scrambled to intercept the enemy Me109s who would have limited fuel supply while over England and the RAF now had 276 Spitfire and Hurricanes in the air. The Germans outnumbered the British in this raid by two to one and for every two RAF planes, there were three Me109s. At Uxbridge, Winston Churchill followed the battle unfolding and famously asked AVM Keith Park ‘How many squadrons have we in reserve?’ to which Keith Park replied ‘None, Sir’.

The action was the climax of the Battle of Britain.RAF Fighter Command defeated the German raids; the Luftwaffe formations were dispersed by a large cloud base and failed to inflict severe damage on the city of London. In the aftermath of the raid, Hitler postponed Operation Sea Lion. Having been defeated in daylight, the Luftwaffe turned its attention to The Blitz night campaign which lasted until May 1941

Kurt Hausberg

As the German formations flew towards their target in London they encountered heavy anti-aircraft fire over Chatham and the Dornier 17 piloted by Lt Herbert Michaelis was hit. The port engine was damaged and the pilot, realising that he could not keep up with the formation and the protection it would give him, decided to return to base. He hoped to use the cloud cover to help him evade the RAF fighters and this idea worked for a few minutes. However, when he reached the Gravesend area 63 RAF fighters were attacking a different part of the German formation and the plane was hit numerous times by RAF fighters and was badly damaged further. It was somewhere at this point that two Hawker Hurricanes from 504Sqn spotted the Do17 and went into the attack on Lt Michaelis bomber.

One Hurricane flown by Sqn Ldr Sample carried out four attacks on the bomber opening up at 200yds then closing down to 75yds, firing 2-sec bursts which hit the bomber with 320 rounds of .303 bullets. In the cockpit, a bullet had struck the dye bag attached to Lt Michaelis’ Mae West to help in case the plane had to ditch in water and the cockpit filled with yellow dye. This temporarily blinded the pilot and, as he attempted to maintain control, he may have thought that the plane was too low and may have given the order for the crew to bale out. In any case, the other engine started to fail with black smoke emitting from it and the crew, sensing that the end was near, decided to bale out.

Two of the crew, Unteroffizier Kurt Hausburg and Unteroffizier Burbulla baled out. Kurt Hausburg was found dead in a field behind Rumney Farm, Ash Road, Stansted where his parachute was found to have only partially opened. Unteroffizier Burbulla landed by parachute and was captured badly wounded. He was taken to West Hill Hospital Dartford where he died from his wounds two days later on the 17th of September 1940.

Hausberg was buried in St Mary’s Churchyard, Stansted and lay there for 22 years until on 23rd October 1962 at the request of the German Government his body was moved to the Cannock Chase German Military Cemetery, Staffordshire.

Sheila Parker who was born and brought up in Stansted in the 1930s and 1940s and has lived in Delatour, Plaxdale Green Road since the early 1970s has recorded her memories of WW2 and these are on this website under People>Recollections>Sheila Parker. She recalls “One Sunday in September 1940 my father came in from the garden and said a parachute was falling unopened “candling” in the Rumney Farm area. As a member of the Home Guard, he hurried there on his bicycle, and when he returned, I remember him saying “the poor man must have broken every single bone in his body”.

In his report on the German Messerschmitt aircraft that crash-landed near St Mary’s church two weeks later on 31st August 1940 “The One behind the Church”, Stansted resident Mark Charnley recorded

“Another ‘mix-up’, which is common in the village, is the belief that the rear gunner of the Messerschmitt, who later died, was buried in the Stansted church graveyard. This is not so. There was a German buried in the churchyard but it was not the rear gunner from the plane behind the church. The airman who was buried was Unterofficer K. Hausburg, a crew member of a Dornier 17 (Flying Pencil) who had baled out and his parachute caught fire and ‘Roman Candled’.

What Happened in Barnehurst

Nigel Staniford relates “At 14:45 the plane came into view over Barnehurst being chased two 504 Sqn Hurricanes pouring fire into the wounded Dornier, around about this time my grandparents who lived at 55 Edendale Road, were preparing to sit down for Sunday lunch as the family were all together as my grandfather was home on leave from the army. In the words of my uncle who was a young boy at the time ‘We were just getting ready to have Sunday dinner when we heard machine guns firing, we rushed out the front door to see a German bomber with black smoke pouring out of one of its engines being chased by two RAF fighters. It just cleared the electricity pylon which was outside the house and we had black smoke billowing into the house as myself and my dad ran into the back garden to see the plane crash onto the golf course. My father and I later tried to walk down to look at the plane, but we were prevented from getting nearby Police. I later found out my friend’s father (Samual Sole) had died in hospital due to the explosion’.

Sqn Ldr Sample later described what happened and what he saw as the bomber crashed.

“An hour later we were in the air again, meeting more bombers and fighters coming in. We got three more – our squadron, I mean. I started to chase one Dornier which was flying through the tops of the clouds. Did you see that film Hell’s Angels? You’ll remember how the Zeppelin came slowly out of the clouds. Well, this Dornier reminded me of this. I attacked him four times altogether. When he first appeared through the cloud – you know how clouds go up and down like foam on the water – I fired at him from the left, swung over to the right, turned in towards another hollow in the cloud, where I expected him to reappear, and fired at him again. After my fourth attack he dived down headlong into a clump of trees in front of a house (Barnehurst clubhouse) and I saw one or two cars parked in the gravel drive in front. I wondered whether there was anyone in the doorway watching the bomber crash”.

After the bomber had crash-landed about 100 yards from the clubhouse, Sqn Ldr Sample performed a victory roll over the golf course to the cheers of the crowd of locals rushing to the crash site from the surrounding areas. After he had done this he was to continue helping to attack enemy bombers that were heading towards London, he managed to help shoot down a He111 which had a forced landing onto RAF, West Malling.

Back at the crash site crowds were coming towards the plane which had small fires burning around and bombs scattered around it, several people were attempting to prevent anyone from getting near to the wrecked bomber. Of the people who were known to be trying was Special Constable Francis Clarke of the Kent Special Constabulary who was seen to be shouting at people to keep back but this was ignored by the locals who were excited to what they had witnessed and possibly wanting a souvenir moved towards the bomber.

Around this time there are reports that Lt Michaelis emerged from the plane slightly wounded and covered in yellow dye warning people to keep back as there were unexploded bombs still on board the plane. I can not confirm whether Flieger Hermann Bormann had baled out or was still in the plane wounded, but he had survived the attack. Lt Michaelis was arrested by Police/Home Guard and was taken away. He was first taken to West Hill hospital Dartford, before being taken to the Royal Herbert Hospital near Shooters Hill where he was placed on the Luftwaffe ward in bed 2 with other wounded German airmen.

A young lad called Gordon Bennett witnessed like my uncle the plane flying at low level from where he was staying at his grandmother and aunt’s house in Eversley Avenue and saw the plane disappear over the hill then seconds later saw the black plume of smoke rise to indicate that the plane had crashed. Dr Bennett, as he later became, wrote his eyewitness account on the BBC website about WW2 in 2005. After his father and himself had walked towards the crash site they made their way across the abandoned orchard which is now the Orchard allotments in Mayplace Road, as the main entrance to the golf course was clogged with people trying to get in. Gordon Bennett states:

“Seeking an easier entry to the crash site, my father led the way to a wooded track, where a brick wall ran parallel to the pathway, a few yards away. We joined the stream of people clambering through a gap in the wall.

A policeman stood nearby, warning everyone that it was dangerous to enter, but his words fell on deaf ears, such was the excitement caused by this unusual event. Tragically, in the course of his duty, that constable was soon to lose his own life.

When we got over the wall, my father told me to stay there, while he went forward to where the wreckage was burning, about 20 yards away. I looked around and saw that I was in a derelict orchard, and I became aware of a low roaring sound, close by. Peering through the undergrowth, I saw, to my horror, that about 10 feet away, a high explosive bomb was lying on the ground, its nose pointing towards the wall. Its fins were missing, and from the broken rear-end a jet of orange-coloured flame was pouring. A small crowd of onlookers had gathered around.

Like many boys at that time, I had absorbed a good deal of information about the construction and functioning of weaponry, so it was hardly surprising that the first thought that came into my mind was that when the burning of the bomb’s contents reached its detonator, there would be trouble! With that, I flung myself face down into a shallow depression in the ground, intending to crawl away. This action probably saved my life, as the bomb exploded at that moment. There was a deafening bang and I felt an overwhelming pressure on my back. This was followed by a torrent of earth and debris. I got to my feet and began to run after my father, with the screams of the wounded ringing in my ears. A boy, older than me, was sitting dazed on the ground, where he had been thrown by the explosion; there was a gaping wound in his leg. My father emerged from the smoke; his face was drained of colour and bore an expression of mixed emotion that I had never seen before. Grabbing my arm, he said “Come on son, we must get away from here”’.

A doctor who was playing golf on the golf course at the time of the explosion attended to the many wounded who were laid out in front of the clubhouse. Newspaper reports state around five people were killed, these were the following:

- Charles William Daniels (Civilian) age 37.136 Parkside Avenue Barnehurst.

- John Frank O’Connell (Air Raid Warden) age 33.163 Parkside Avenue Barnehurst.

- William Taylor (Civilian) age 72. 262 Parkside Avenue Barnehurst.

- Constable Francis Leonard Clarke (Kent Special Constabulary) age 28.156 Parkside Avenue Barnehurst.

- Samuel Ernest Sole (Air Raid Warden) age 39. 202 Parkside Avenue Barnehurst.

Squadron Leader John Sample, DFC

The Hurricane which was leading the attack was flown by Sqn Ldr John Sample from Morpeth, Northumberland. He had been born in February 1913 and had been a land agent in civilian life working with his uncle. He had joined the AuxAF in April 1934 and by the time his Squadron had started to be re-equipped with Hurricanes in April 1940 he was an experienced pilot. He had been shot down in a previous engagement and had parachuted to safety but had sprained both his ankles severely on landing. Thereafter, until recovery, he had been obliged to wear carpet slippers at all times, even when flying.

He was awarded the DFC on 4th June 1940 for his actions in France. His citation stated that he had been an inspiration to his squadron and, on 1st September he was promoted to Squadron Leader. On 5th September the squadron moved south to Hendon, northwest of London, to take part in the Battle of Britain.

By 15th September 1940, he had six aircraft shot down and shared kills to his name. On that day he had been in the thick of the battle most of the day and he had shot down a Do17 in the morning to add to his tally. In this battle Sergeant Roy Holmes famously rammed a Do17 while out of ammunition which had just bombed Buckingham Palace, the bomber crashed onto Victoria railway station. Sgt Holmes landed on the roof of a block of flats next to the Victoria coach station, his parachute caught on the drain pipe and ripped, slowly until he was standing in a dustbin next to the block of flats.

Tragically, John Sample was killed the following year during a practice flying session near Swindon. His aircraft was seen going down out of control, with part of the tailplane coming off. The machine was in a spin, and when close to the ground, Sample was seen leaving his machine but his parachute canopy did not open, and he landed on the roof of some farm buildings (Manor Farm) near Englishcombe and was killed. His aircraft landed on the same buildings and burst into flames. He was buried in St. Andrews churchyard Bothal, Ashington Northumberland on 28th October 1941 aged 28.

The Crew of the Dornier

The Dornier had a four-man crew with these details:

Herbert Michaelis – Pilot Lt aged 22 from Braunschweig. Michaelis had fought in the Polish and French campaigns and had recently been a teacher at a flying school. He was flying his first mission to England. He was slightly only slightly injured in the action and was arrested and taken to hospital. He was later questioned at Trent Park. After they had got all the information they could from him he was transferred to pow camp 15 (a hotel called Shap Wells, Kendal, Cumbria). Intelligence advised that there were possible plans for the pows to stage mass breakouts if an invasion happened and this would cause problems for the British government as they would be fighting battles on two fronts as the pows fought their way to reach the invasion force. As a result, it was decided that all pows would be transferred to Canada where camps were built to house them. After a stay in Canada Lt Michaelis was sent back to Germany in 1947 after the war had ended and he died in November 1995 aged 77.

Hermann Bormann – Rear gunner Flieger aged 21 from Gladbeck. Bormann was a carpenter by trade and was the gunner that day. He was seriously injured and was captured with gunshot wounds to the face and thigh. he was first taken to Preston Hall Hospital Maidstone, before being transferred to the Royal Herbert Hospital Woolwich, after he had recovered he was sent to camp 80 at Horbling, Sleaford in Lincolnshire. There was a spell in Canada before he was sent back to Germany in 1947 after the war had ended. He died in 1987 or thereabouts aged 67.

Kurt Hausburg – Observer/gunner Unteroffizier aged 30. Born in Dortmund on 8th November 1911 and married to Helene when the war started, Hausberg was, at the age of 30, the old man of the crew. An RAF intelligence report stated that crew morale had been high on that day as the bombers flew over the English coast, but this soon disappeared when the port engine was damaged by AA over Rochester and panic settled in once RAF fighters were spotted.

In the ensuing firefight, the other engine was damaged by the fighter attacks. With the bomber seriously damaged the crew tried to get back to France but were chased by RAF Hurricanes. As the plane reached Stansted in its attempt to escape the fighters, either the crew were ordered to bale out or sensing that the end was near, Hausberg baled out on his own initiative. The plane was too low, however, and his parachute failed to open. He was killed as he landed in a field behind Rumney Farm.

Once Hausberg’s body was found he was buried in St Mary’s churchyard Stansted on the 17th September 1940. 22 years later on 23rd October 1962 at the request of the German Government, his body was moved to the Cannock Chase German Military Cemetery, Staffordshire. He now lies in Block 1, Row 7, Grave 247.

Wilhelm Paul Burbulla – Radio Op Unteroffizier aged 23 from Liebenberg, East Prussia. He was the radio operator on the bomber that day and was badly wounded in the fighter attack. He baled out in the local area and was captured and taken to West Hill Hospital Dartford where he died two days later on 17th September 1940.

He was buried in Watling Street cemetery, Dartford and in October 1962 he was removed like Kurt Hausberg to the national German cemetery at Cannock Chase in Staffordshire where he is resting in Block 5, Row 3, Grave 51.

Aftermath

The plane on Barnehurst Golf Course was guarded by the authorities and for days after members of the public were prevented from seeing it. The RAF intelligence section combed the plane for anything of interest and the remaining bombs were defused and taken away. The only intelligence they found of interest was the pink bars found on the wing which were formation bars for other planes to form up when flying. The plane was eventually dismantled by recovery crews and taken away.

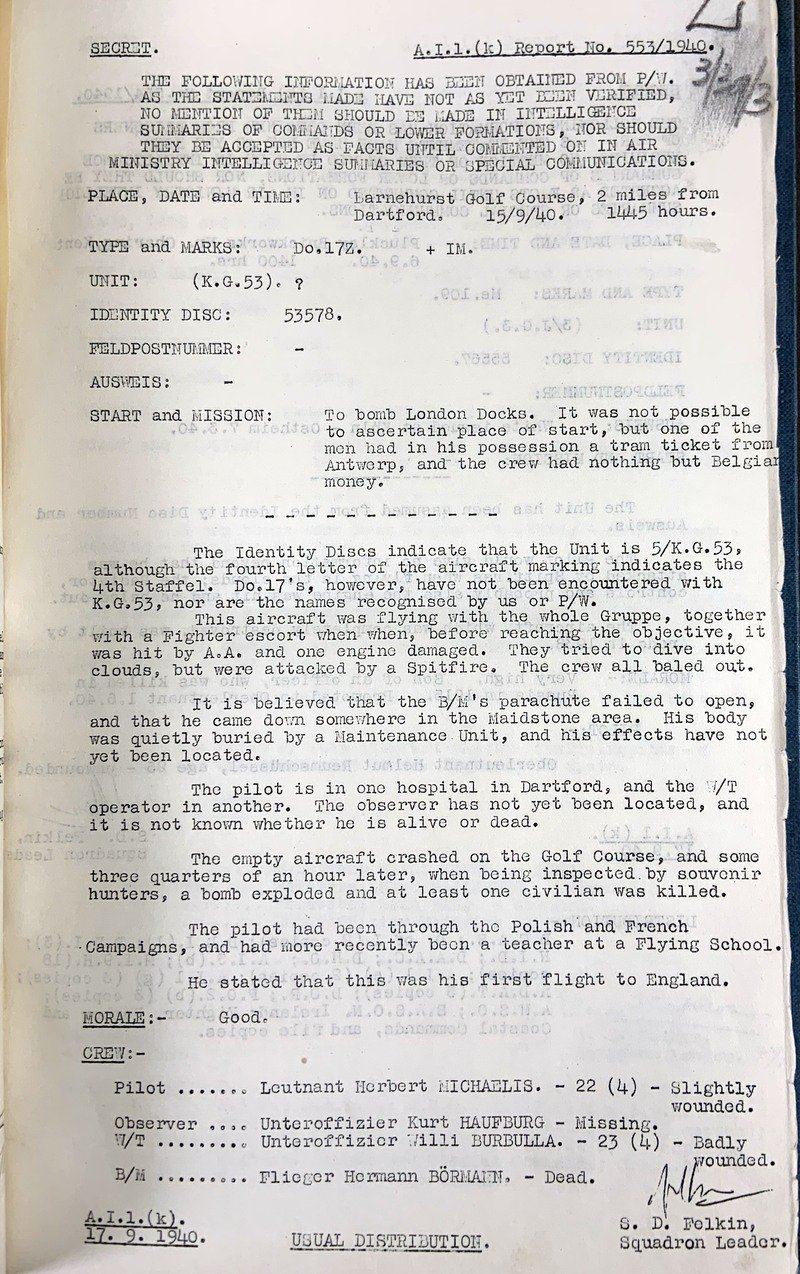

After Lt Michaelis had recovered from his wounds he was transferred to Trent Park near Cockfosters London which was a stately home being used to house POw’s which was bugged with microphones so that the intelligence authorities could listen in to the prisoners speaking to each other so to try and gain any intelligence which could prove useful to the English in their fight against the enemy. This operation was run by Squadron Leader Denys Felkin, the father of Anne Walton who lived at Stansted Lodge Farm, Tumblefield Road, Stansted for many years. The Intelligence report on the incident prepared and signed by him is shown in the accompanying image.

So on 15th September 1940 great events were happening in the skies above the Parish and, arguably, the tide of the whole war turned on who succeeded and who failed that day. Down below, however, the normal rural life of Stansted continued with animals being tended and crops being harvested. Only a distant memory of a lone parachute and the grave in the churchyard with a German name on it remained. Other than that…scarcely a ripple. The futility of war, indeed.

Author: Dick Hogbin

Editor: Tony Piper

Contributors: Nigel Staniford

Last Updated: 31 October 2021